Get posts by email

Losing what we never had: A settler-descendent search for a sustainability ethic

September 28, 2021

Just a heads up for my regular blog readers, this post is an assignment for school. So you'll notice it has a different tone and feel to what I normally publish (and references!). And lucky for you, it's a much quicker read than my usual posts. I'm delighted that my classes enable me to explore topics like this (that's why I'm in grad school) and that I'm given assignments that can be posted to my blog, "create a multimedia digital text"... So much fun!

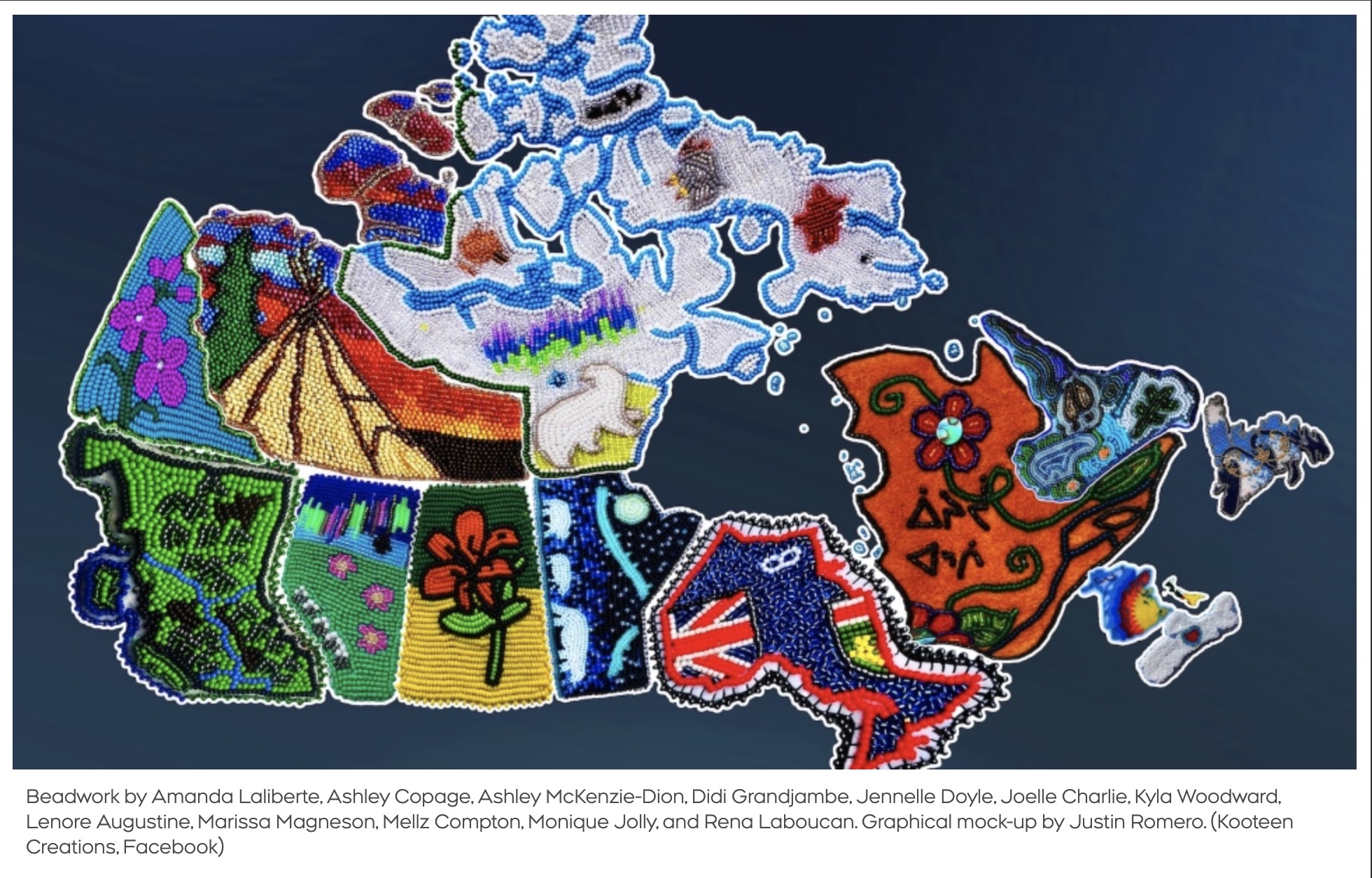

Image credit: Seven Allies & #beadyourprovince

The quest for land

I am the lucky descendent of European immigrants to Canada. I say lucky because my ancestors were the ones that lived through the personal, collective, and cultural losses that assail each generation and individual, according to its own time and place in history. My ancestors determination to make a new life for themselves, a life that promised religious freedom and land that would feed and sustain their children and their children’s children, is why I’m here today.

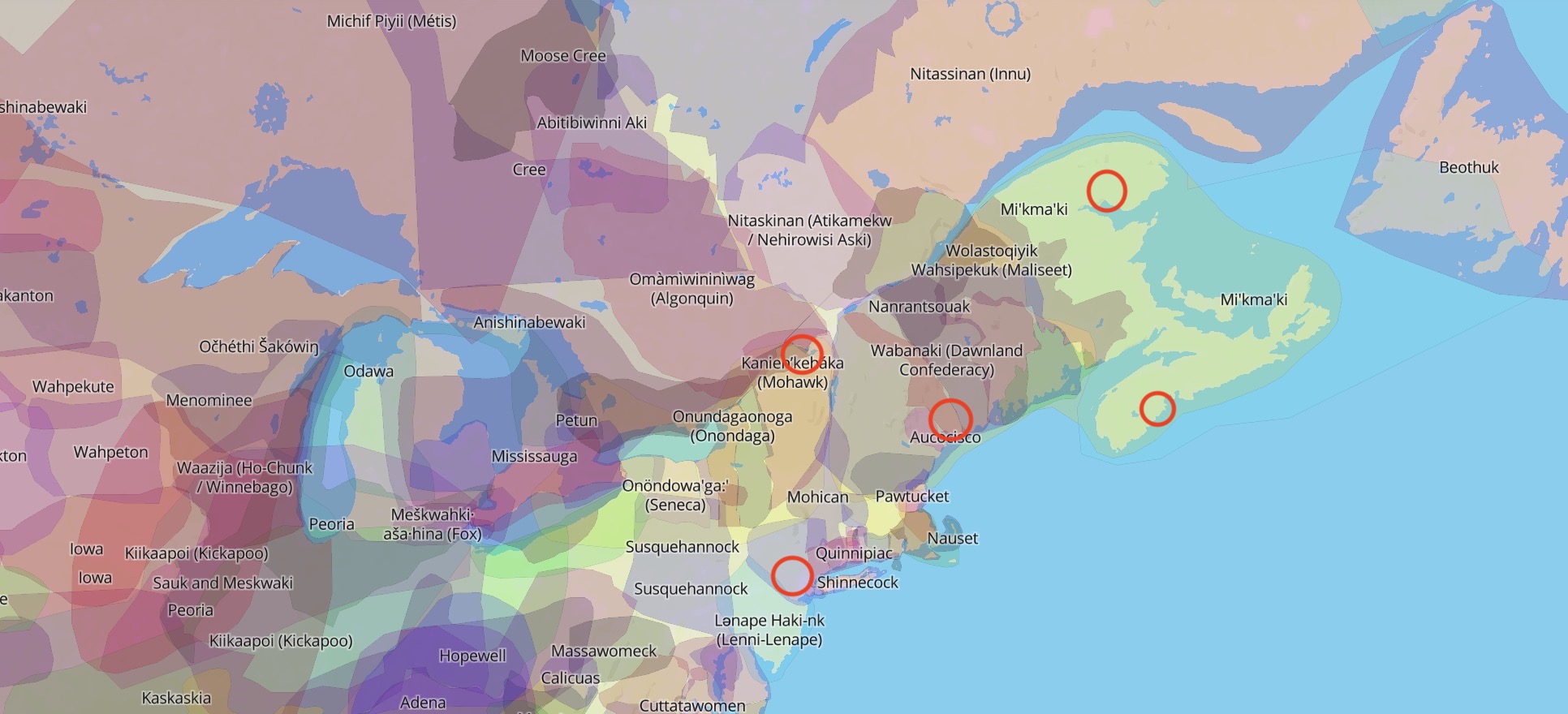

Born and raised in Treaty Six Territory, I have lived my adult life in the unceded territories of the Munseeh Lanape, the Wabanki Confederacy (specifically in Abenaki, Arosaguntacook and Mi’kma’ki lands). I currently live on the unceded territory of the Kanien’kehá:ka (Native Land Digital).

The irreconcilable irony of my origin story to Turtle Island is that my great-great-grandparents and great-grandparents were themselves displaced by European primitive accumulation of capital and religious persecution and were seeking land on which to grow food, raise their children, and practice their religion in peace (Nikkel, 2019). These seemingly innocuous and universal aims were only made possible by dislocating and dispossessing the original inhabitants of this land who had been living according to similar motivations with regards to sustenance, spiritual practice, and harmony, for many, many generations.

I don’t point out my own ancestors' dislocation and dispossession as an attempt towards settler innocence (Tuck & Yang, 2012). I state all this because it is my heritage and it informs my worldview.

White settler migration to Turtle Island was driven by a quest for land, freedom, and resources. Now, having damaged the land, air, and water, and facing an existential threat of human-caused climate change (Tougas, 2021), we have a new quest to fix the mess we made, the quest for sustainability (Mulligan, 2018; Robertson, 2012).

How did we get here?

Colonial nations like Canada perpetuate a geo-political and economic narrative of land as property which can be owned, improved, bought, and sold; whose resources can be extracted. This story, and the political, social, and economic structures that flow from it, informs our relations with not only the land but with each other and all beings. And it is this story that both created the problems we’re facing and complicates our ability to solve them.

Please watch the section from to 0:13 to 2:40.

From “Dismantling the Doctrine of Discovery” (Assembly of First Nations, 2018)

The Doctrine of Discovery emanates from a series of Papal Bulls (formal statements from the Pope) and extensions, originating in the 1400s. Discovery was used as legal and moral justification for colonial dispossession of sovereign Indigenous Nations, including First Nations in what is now Canada. During the European “Age of Discovery”, Christian explorers “claimed” lands for their monarchs who felt they could exploit the land, regardless of the original inhabitants.

This was invalidly based on the presumed racial superiority of European Christian peoples and was used to dehumanize, exploit and subjugate Indigenous Peoples and dispossess us of our most basic rights. This was the very foundation of genocide. Such ideology lead to practices that continue through modern-day laws and policies.

Please watch the section from 26:35 to 27:55.

Humility on the quest for sustainability

As Sumner (2005) points out, geo-political and economic structures, like those that inform the Canadian narrative, hamper our efforts towards sustainability. I would add that the religious arrogance of The Doctrine of Discovery was largely responsible for creating the sustainability crisis we face. (I say this as a professing Christian.) And that as a pluralist, post-modern society that has necessarily rejected exploitative religion (good bye and good riddance), our sustainability ethic and efforts lack a socially cohesive spiritual dimension that would potentially rally large numbers of people to affect change.

Indigenous sustainability ethics are unique and differentiated from post-modern definitions of sustainability (Hensley, 2011; Sumner, 2005) in that they depend on a spiritual dimension, not as an addendum but as the foundation (Prosper et al., 2011; Kimmerer, 2013)

The sad irony of course is that settler culture, driven by the Doctrine of Discovery, advanced unsustainable practices which created our current crisis, by displacing and dispossessing the original inhabitants whose relationship with the land, anchored in their own spirituality, is inherently sustainable.

Colonial and settler culture and practices sought to eradicate the very people who’s ethic is part of the solution for our own problems.

Can we do it for our children?

I am the unlucky descendent of European immigrants to Canada. I say unlucky because the dominant culture to which I belong did not inherit an ethic of sustainability as part of our religious and spiritual practice. Instead, our religious arrogance contributed to the environmental degradation that now motivates our quest for sustainability. Collectively, we are seeking a sustainability ethic without a spiritual anchor. So we appeal to economic, ecological, and social imperatives. It’s all we’ve got.

For me, this lack of spiritual impetus and collective anchoring is a loss. But there is hope in seeking solutions that enable the flourishing of our children. All our children.

The reconciliation efforts in the land claim between the Young Chippewayan First Nation and settler-descendents in Laird, Saskatchewan is one example.

Click here to see the video embedded on this page and watch from 4:35-6:00.

I close these thoughts with the words of Philip Blake, a Dene from Fort McPherson, as quoted by Coulthard (2014, p.72).

I strongly believe that we do have something to offer your nation, however, something other than our minerals. I believe it is in the self-interest of your own nation to allow the Indian nation to survive and develop in our own way, on our own land. For thousands of years we have lived with the land, we have taken care of the land, and the land has taken care of us. We did not believe that our society has to grow and expand and conquer new areas in order to fulfill our destiny as Indian people.

We have lived with the land, not tried to conquer of [sic] control it or rob it of its riches. We have not tried to get more and more riches and power, we have not tried to conquer new frontiers, or out do our parents or make sure that every year we are richer than the year before.

We have been satisfied to see our wealth as ourselves and the land we live with. It is our greatest wish to be able to pass on this land to succeeding generations in the same condition that our fathers have given it to us. We did not try to improve the land and we did not try to destroy it.

That is not our way. (emphasis added)

We have much to learn. We don’t have a lot of time to learn it. It is my greatest wish that Canada’s post-modern sustainability ethic will be informed by Indigenous relations with the land, each other, and all beings. And in doing so, we’ll create a future that will sustain our children and our children’s children.

References:

Assembly of First Nations. (2018). Dismantling the doctrine of discovery. http://caid.ca/AFNDisDocDis2018.pdf

Coulthard, G. (2014). Wards of the state to subjects of recognition?: Marx, Indigenous peoples, and the politics of dispossession in Denendeh. In A. Smith (Ed.), Theorizing Native Studies (pp. 56-98). New York, USA: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822376613-005

Hensley, G. (2014). The scholarship of sustainability. In, Curriculum studies gone wild: Bioregional education and the scholarship of sustainability (pp. 95-134). Peter Lang Publishing, Inc. New York.

Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge, and the teachings of plants. Milkweed Editions.

Mulligan, M. (2018). An introduction to sustainability: Environmental, social, and personal perspectives. Routledge.

Native Land Digital. (n.d.). Native Land. https://native-land.ca/

Nikkel, J. (2019). White settler dysconsciousness and ethnicity – Constructing innocence and non-complicity among Mennonites and other white settlers in Canada [Masters thesis, University of Alberta]. https://doi.org/10.7939/r3-y7bp-8g52

Prosper, K., McMillan, L. J., Davis, A., Moffit, M. (2011). Returning to Netukulimk: Mi’kmaq cultural and spiritual connections with resource stewardship and self-governance. The International Indigenous Policy Journal. 2(4), https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2011.2.4.7

Robertson, M. (2012). Sustainability principles and practice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429346668

Sumner, J. (2005). Sustainability and the civil commons: Rural communities in the age of globalization. University of Toronto Press. https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442684843

St. Johns Lutheran Laird & Mennonite Central Committee Saskatchewan. (2016, August). 40th anniversary of the signing of Treaty 6. [Video]. Reserve 107: Reconciliation on the Prairies. https://www.reserve107thefilm.com/copy-of-study-guides-resources

Tougas, R. (2021). Global warming and the disproportionate impacts of climate change on the global south. [Unpublished manuscript]. Concordia University.

The Anglican Church of Canada. (2019, April 11). Doctrine of Discovery: Stolen lands, strong hearts [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mQwkB1hn5E8&t=1677s

Tuck, E. & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, & Society, 1(1), 1-40

Filed Under

You can subscribe to comments on this article using this form.

If you have already commented on this article, you do not need to do this, as you were automatically subscribed.