Get posts by email

Is localism the answer?

March 27, 2023

This is part two of an essay divided into four parts for easier blog reading.

You can read the entire essay in pdf version here.

I’ve also produced an audio recording the complete piece. It’s 1 hour long.

↓ Audio recording of essay↓

Conclusion of first installment:

As my story illustrates, these cultural discourses and systems contribute to people uprooting and relocating. Experiences that can amplify the individual and collective sense of dislocation, and disorientation, spurring the question, “where is home?”

Some people’s answer to this question is, “if we all just stayed put we’d be better off.”

This brings me to Wendell Berry, farmer, writer, philosopher, and localism activist.

Is localism the answer

I’ve been reading Berry since the aughts. Those were the days of my “organic” and green awakening in which I thought I might become an urban homesteader. Short of that, I could make all my soaps, vermicompost in my basement, reduce energy consumption, cook all our food from scratch, and maybe even eliminate toilet paper from our lives. (Family cloth: Google it.)

Berry’s poetry, short stories, novels, and essays are a call to local community and local land. I love his writing for many things: his anti-war and anti-violence stance, his critique of capitalism, his staunch advocacy of familial responsibility and fidelity, and his love for land and place.

Berry is a moral philosopher who argues for particular axioms and practices of what constitutes a good life in his writing and living. And I happen to agree with many of them.

His well-founded criticisms of globalism and capitalism undergird a localism response to the question, “where is home?” However, I get the sense when reading Berry that he feels if people just stayed put we’d collectively and individually experience less dislocation. That “staying” would resolve the problems associated with migrations.

I disagree.

Berry’s localist analysis and vision are woven throughout his work. Still, they are perhaps most explicit in his 2012 Jefferson Lecture for the National Endowment for the Humanities entitled “It all Turns on Affection”. Borrowing the terms Stickers & Boomers from his mentor Wallace Stegner, another American writer/philosopher I also enjoy reading, Berry categorizes the American experience of migration and movement into a binary reality. There are those that stay, the Stickers, and those that leave, the Boomers.

“The [B]oomer [ostensibly looking for a “boom” in wealth] is motivated by greed, the desire for money, property, and therefore power (note added).”

“Stickers on the contrary are motivated by affection, by such love for a place and its life that they want to preserve it and remain in it.”

Unfortunately, according to Berry, “[b]y economic proxies thoughtlessly given, by thoughtless consumption of goods ignorantly purchased, now we all are [B]oomers.”

Berry provides more context.

“Boomer” names a kind of person and a kind of ambition that is the major theme, so far, of the history of the European races in our country. “Sticker” names a kind of person and also a desire that is, so far, a minor theme of that history, but a theme persistent enough to remain significant and to offer, still, a significant hope.

Although American and Canadian history is different, there’s enough similarity in, and frankly, dominance of American culture in the North American landscape to apply this to the Canadian context also.

Admirably, Berry is a doer and a thinker of deep conviction who aligns his actions with those convictions. However, I am deeply skeptical of any binary accounting of human social experience divided into “this or that”.

Neither Boomer nor Sticker narratives account for most of the motivations of immigration to North America. This fact, as well as the barely acknowledged discomfiting tension that Berry’s own Kentucky homeland was secured in the not-so-distant past by the displacement of the original Sticker Indigenous inhabitants, constitutes my chief criticisms of Berry’s positioning the Sticker mentality as the morally superior answer to modern human settlement and migration.

Berry is saying that resource extractions, migrations, and land acquisitions of European peoples and their descendants, and the attendant Indigenous displacement within North America, were driven by a Boomer mentality. I agree that greed and the desire for capital, property, and power were underwriting influences of European exploration and expansion into North America starting in the late 16th century when Europeans started fishing for cod on Newfoundland’s Grand Banks.

These motivations ring true on the macro level, where policies are enacted by monarchs, emperors, oligarchs, and nation-states. The narrative breaks down, however, in the lived migration experiences and motivations of individuals, families, and communities whose lives are often pawns on the geopolitical and economic chessboard.

One story from my own ancestry

My ancestry includes ethnoreligious Mennonites who arrived in Canada as religious refugees in the late 19th century.

The Mennonite religion emerged from the tumult of the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. Its leader Menno Simons was a Dutch Catholic clergy before founding this eponymous Christian sect.

This religion belongs to the Anabaptist tradition and is defined by a particular doctrine and confession of faith and includes a “literal interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 5–7, which teaches against hate, killing, violence, taking oaths, participating in use of force or any military actions, and against participation in civil government” (Wikipedia).

There is an explicit non-conforming to the kingdom’s of this world imperative in this religion. These are my roots.

Due to their convictions to “not provoke or do violence to any man… even, when necessary” Mennonites faced regular persecution, including heavy taxation, and were forced to migrate from their origins in German-speaking Switzerland and The Netherlands (Dawson, 1936).

Further, as noted by Dawson, migration was also a way to resolve “group crisis” and the frequent schisms of orthodoxy within the Mennonite faith. Communities would splinter along a conservative-liberal axis, and the more pious group would migrate en masse to a new location, physically removing themselves from the inroads of secularization in the existing community.

This pattern of moving to remain religiously pure continued into the 20th century for some Mennonite and other Anabaptist religious communities.

In the modern-day context, Mennonite is an Anabaptist-based branch of Christianity whose adherents or members come from varied ethnic and cultural backgrounds. There are Mennonite congregations worldwide that speak the local language and are constituted by the cultural and ethnic inhabitants of that area. E.g., Ethiopian or Indian Mennonites. But Mennonite is also an ethnic or ethnoreligious designation, defining a group unified by common culture, language, ancestry, and religion.

My Mennonite background is of the latter. In other words, it wasn’t just a religious belief; it was an ethnicity. My paternal grandfather’s ancestors were converts to the Anabaptist belief, and they made 3 migrations. First to East Prussia (modern-day Poland), then Russia (modern-day Ukraine), and finally to Southern Manitoba, Canada, in the late 19th century.

My great-great-grandparents came to Canada as members of a group with a shared culture, language, background, and religion. Their ties were not to a place but to a set of beliefs and practices that defined their identity.

cabin on a recent snowshoe backpacking trip

Macro geopolitical forces, including those that displaced the Indigenous people who used to steward Berry’s Kentucky farm or the southern Manitoba land my ancestors settled, and sweeping changes in culture, like the Protestant Reformation or the Industrial Revolution, are forces that uproot individuals, families, and communities from their place of origin.

But these are not the only reasons people migrate.

The impulses and physiology that motivate and drive human behaviour are the same today as they have been for a long, long time. We haven’t evolved from them, and transhumanism and genetic engineering have yet to take us there.

Humans have constantly been acquiring new views of ourselves and our environments, ways to manipulate both, and methods of communicating those understandings. Culture, tools and technology, and so much else have advanced. But we, as biological Homo sapiens, remain the same, for now.

And we need the same things our distant ancestors needed: security in group belonging, food, shelter, and stories to make meaning of the cosmos and our place in it.

We migrate because we are seeking security and resources. We migrate because we make up new stories that call us to new places. We migrate because we’re curious and highly adaptive beings. This is the human way.

As a species, we push boundaries, sometimes in pursuit of exploitative accumulation of power; hello, colonialism. But sometimes, in the quest for new understandings or solutions to problems. We’re always looking for new horizons to explore, new resources to access, and easier ways of securing our needs.

This does not automatically make us Boomers. It makes us Explorers.

Berry describes Stickers as having “an ethic of affection” for place. And of Boomers being motivated by rapacious greed. But there is way more to the story of migration than these two ideas. More to us, as a species and individuals, than one or the other.

Is conservation the answer?

In one of my recent political series posts, I talked a bit about a conservative mindset. In modern political parlance we frame being conservative as an expression of behaviour or belief along a particular fault line of issues. Conservatives think x about an issue, and Progressives think y. But conservative, as an adjective, simply means you want to conserve the way things are. It’s an outlook independent of current political constructs and ideologies.

A conserving position seeks to conserve what is known. It is respecting of tradition, stories, and ideas from the past.

This is fundamentally important for human survival and thriving. We pass on knowledge so we don’t have to learn afresh with each new generation.

The non-conserving position seeks to push the boundaries of what is known, both physically and non-materially.

This is fundamentally important for human survival and thriving. We move beyond established cultural knowledge and limits, including physical location, so we don’t stagnate as individuals or populations.

The arch-conserving position is that we are bounded by outside-the-system limits that are ideologically based. There are some good reasons humans have constructed and appealed to these limits to keep other humans in check. But this position loses its credibility when it’s ultimately abused by those seeking to exercise power over others and when people stop believing the particular story that scaffolds the ideology.

While writing this piece, I came across the most salient example of an arch-conserving position on migration in the Winter 2023 edition of Plough. The essayist Laverty writes, “God has marked out our appointed times in history and the boundaries of our lands, and commands us to remain as we were when we were called.”

The arch-liberatory position is that there are no limits. Everything, every place, and every experience are for our taking, which leads to exploitation and a wake of destruction.

The conserving position’s weakness is insular ideas and a cap on individual and collective flourishing because this is how we’ve always done it. On the other hand, a non-conserving orientation needs an ethic for limits, where and when are they appropriate, how do we decide, and who makes those decisions?

Migrations challenge the conserving position.

Let’s imagine these scenarios.

Scenario one: A family, a clan, or a contingency of the clan sits around a table, a hearth, or a fire. They talk about a social, political, environmental, or resource problem they’re facing. It’s getting colder, or, it’s getting warmer, the animals aren’t coming in the same numbers any more, the crops aren’t growing as well, etc. There’s a debate amongst the group, with some voices saying, “This is where we’ve always lived. Next year will be better.” Another contingent says, “I heard a rumor that the conditions are better in the east. We should go now.”

Scenario two: A family, a clan, or a contingency of the clan sits around a table, a hearth, or a fire. Someone or someone’s starts talking about social, political, environmental, or economic ideas that are novel to the group. Exploring or testing these ideas requires a certain openness to trying new things. There’s a debate amongst the group, with some voices saying, “This is the way our mother’s mother’s mother’s mother did it, and this is how we will continue.” Another contingent says, “We need to explore this new horizon.”

The problem, of course, is that we no longer live in the distant and not-so-distant past where perceived or actual greener pastures or virgin territory exists beyond the horizon, just waiting to be discovered and settled by disgruntled or simply curious groups of humans. We live on a populated and settled Earth.

Although the quest for differentiation and pushing boundaries and limits is innately human, the Enlightenment was like a starting gun, ready, set, go, for the race to maximize individualism. The technological advances of the past couple hundred years have been fuel on the fire.

Some people think this conflagration will be extinguished with societal collapse and crisis. Others believe we can “technology” our way out of it.

Can we live in mutually flourishing ways?

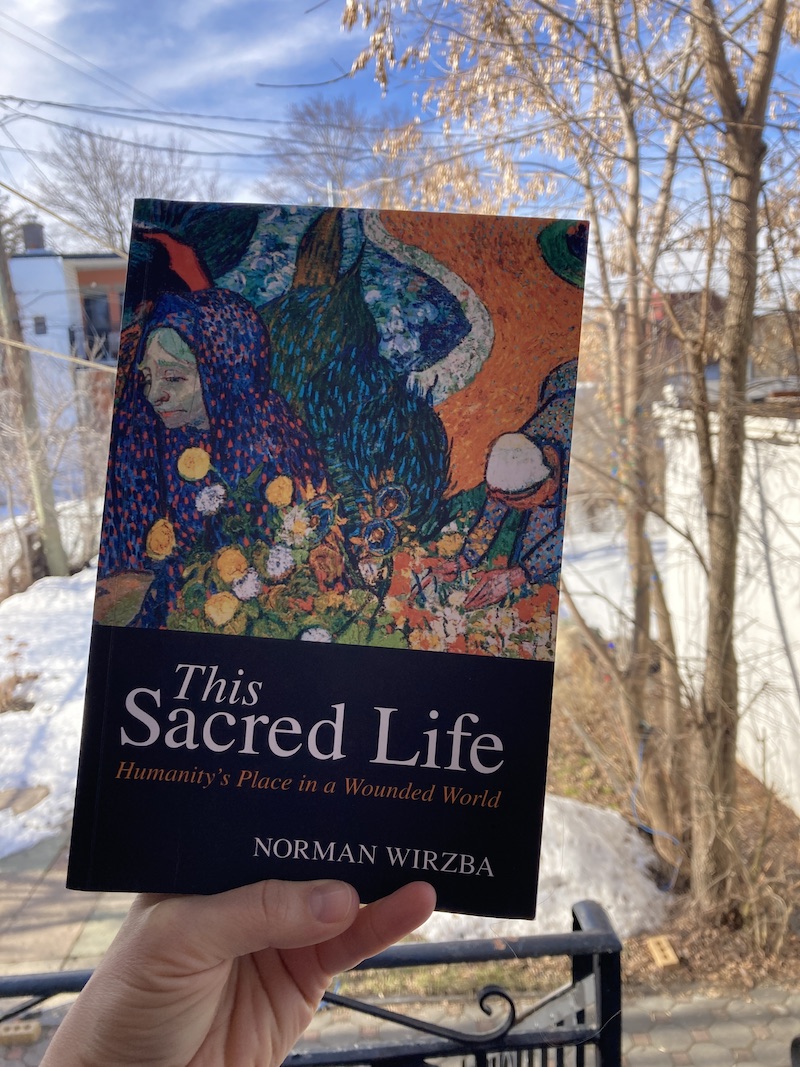

In his book, This Sacred Life, Wirzba argues that “many of the world’s dominant cultures have done a poor job of teaching their people to live in their places in mutually nourishing ways (emphasis mine)”.

I couldn’t agree more, and this statement contains cause and remedy for much that ails us individually and collectively. We don’t live in mutually nourishing ways, human to human, human to other beings, human to land, population to population.

We deny our interconnectedness. We use power advantages, including technology, to exploit the other.

The answer to this is not a commandment to “stay or live in your place”, a position justifying untold abuse and exploitation of other humans when human relations are conceived in hierarchical power structures.

Nor is the full answer, as advanced by Berry and others, to have such a love for place and its life that you commit to preserving and maintaining it. That’s a piece of the answer, but not the whole.

It’s not just an affection for place that keeps people in a location but knowing they belong to that place even if their ideas challenge the bounds of community norms. Human communities must make room for new understandings, developments, technologies, and ideologies. This is how humans solve problems and grow as individuals and as a species.

Throughout the ages, humans have resolved the conflicts of conserving vs. non-conserving viewpoints through not just physical migration but ideological migrations. And ideological migrations are sometimes only made possible by physical migrations.

We can go back to my Mennonite ancestors for an easy example. If a person is born into a very conserving ideology or belief system - this is how we’ve always done it - the only way to explore and express a non-conserving point of view is to leave. Whether it’s the Catholicism from which Menno Simons splintered or the Mennonite sect he founded, both groups want to conserve their beliefs.

For some individuals, the status quo position is religiously, economically, ideologically, or otherwise oppressive, exploitative, or just not a fit for who they are. And the only way to find flourishing is to leave.

It’s true that we can no longer live as if there aren’t limits, as if there is still terra incognito on Earth. But if we’re making an effort to live connected to creatures and places, we must be honest about the need for an ecological reality, not to mention spiritual and political, of diversity in place. A mutual flourishing ethic allows for and is, in fact, dependent upon this diversity.

Human cultures draw limits around the diversity tolerated in a particular place. Establishing those limits based on mutual flourishing is a very different approach than upholding limits based on tradition. Although most cultural practices start as a means to ensure the group’s thriving, these traditions must be scrutinized when they fail to consider out-of-group flourishing, don’t account for human development and evolution within the group, and can’t sustain diversity.

from my Montreal neighborhood

There is angst in the zeitgeist, a collective handwringing about what we should do about rootlessness, alienation from place, and people feeling dislocated and displaced through modern migration. A simplistic and arch-conserving answer points to those that leave as the problem. A more accurate and nuanced answer points to the discourses that drive modernity, including individualism, globalism, and capitalism, as the problem.

Localizing social change movements abound in response to these discourses. And there is a lot of hope in this answer. But only if these localizing solutions are clear-eyed about the problems of communities accepting diversity among their members.

Those trying to affect a cultural change where people are committed to place will need an openness to human diversity that allows for growth in situ.

Natural dissonance and disagreements occur at all levels and between all members of a place, human and other-than-human. What is the principle or ethic by which these are resolved? Humans have a long history of subjecting one another to artificial limits based on non-material reality (i.e.: ideology) and our growth as a species and individuals has required pushing against these limits. What is the principle or ethic that defines the boundaries of acceptable ideas?

In an Enlightenment-influenced and technologically-enabled world, a commitment to live in place in mutually flourishing ways requires an openness to diversity that challenges human institutions and social structures.

Berry’s affection for place is not the whole answer to migration and its attendant rootlessness. Our commitment must be to the flourishing and nourishing of all the beings in that place. And beings, by their very organic and biological nature, grow and evolve, individually and collectively. Places and communities need to either hold space for and accommodate this or we make accommodations for migration and movement.

In summary, migration is not the problem of our species. It’s how we act in the places we inhabit. And how we act depends on what we believe about ourselves, our identity, and our relationship with everything around us.

To be continued, next post.

Subscribe to my mailing list for free, to get the next installment of this essay delivered directly to your inbox.A year after publishing this essay I stumbled (via Blake Boles Substack) upon There are no pure cultures by Inanna Hamati-Ataya, published on Aeon. This is partly what I am speaking to in my reflections on my own moves and migration. I want to link to that article here as a related piece for those interested in the topics of localism and globalism, and especially for those who wrestle with the idea of which is "natural" to the human species.

Part of Series

You can subscribe to comments on this article using this form.

If you have already commented on this article, you do not need to do this, as you were automatically subscribed.