Get posts by email

It all started with a move

March 21, 2023

This and the next 3 posts are the capstone for the blog series and podcast interviews entitled Finding Home.

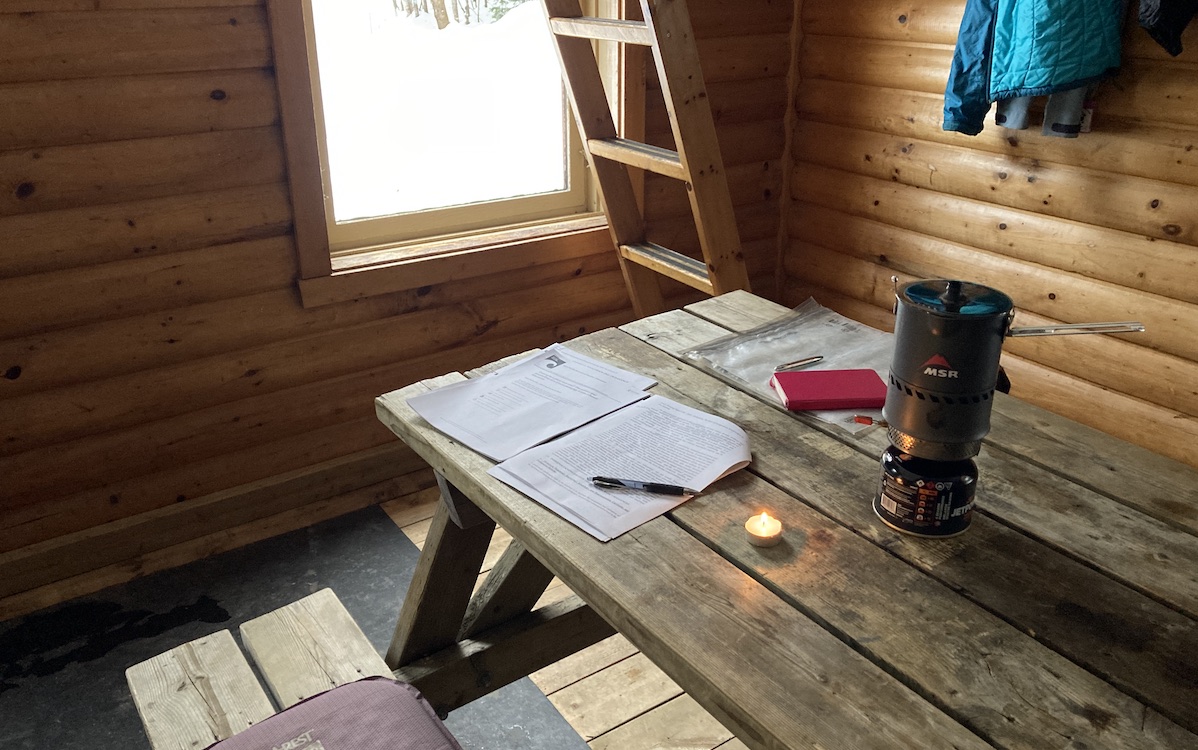

Sanctuary, early March 2023

As a memoirist writer they are more than a writing project, these posts tell the story of my life and in that respect they are a capstone on a personal journey.

I’ve been on a quest for years to answer the question, “where is home?”. That drive motivated me to conduct interviews in 2020 with seven ordinary, extraordinary people about their conception and experience of home.

The knowledge gained from those conversations has influenced my own understanding of home and helped me, in part, find the answers to this question.

I recommend listening to those interviews as a complement and background for this writing but also as a small sampling of the diversity of human experiences around the subject of this essay.

This essay is divided into 4 blog installments for easier reading. However, I also produced a pdf version in its entirety, as it was originally written and intended to be read.

You can open and download that pdf version here. You might prefer that reading experience, especially if you like to read printed materials.

I’ve also produced an audio recording of me reading the entire essay. It’s 1 hour long.

↓ Audio recording of essay↓

First, a note on the evolution of my writing and accessibility of ideas

I started part-time graduate school two years ago. Sometime next year, I’ll finish with a Master of Arts in Educational Studies. This work and effort energize and satisfy me in ways I had not anticipated and wouldn’t have even hoped for.

I'm in a remaking and reimagining phase of life. And going back to school has helped me acquire a language and frameworks for ideas, inklings, and tensions I could previously only feel, but not articulate. I have a whole lumberyard of ideas now at my disposal with which to build understanding.

I have incorporated this language into my writing. How can I not? Words that explain ideas are the Holy Grail for the writer. They are the thing we chase, always looking for an approximation to describe our reality, an experience, an idea that is more precise, closer to the truth than the last. “It’s like this… no, it’s like this… oh! it’s like this…” is a loop I go ’round and ’round, grabbing onto concepts and words, like handholds on an adventure ropes course named “Truth Quest”.

I recognize my writing has gone through a transition while I have gone through a transition. Nevertheless, I need those words to explain my experience, and I don’t want to leave them out or dumb them down in an attempt to make my writing more accessible or relatable.

Instead, I hope that the concepts and frameworks I share, woven into my own story, help others access a more full vocabulary with which to understand of their own experience, which may be counter, contrary, or incongruous to my own.

If I use a word or concept that is new to you that I don’t explain in the text itself, maybe you can employ a strategy I’ve used in my studies. First, I look to see if I can guesstimate the word’s meaning through context or multiple instances in the text. I will also google search the meaning of words, which usually gives me a basic understanding. I also look for occurrences of the idea in other things I’m reading, watching, or hearing. This is a weird one because once I start looking, I often see a new-to-me word or idea popping up in a lot of places. Finally, not in an ordinal sense but in addition to all the rest, I ask for clarification and definition directly from someone using that concept in their teaching, writing, and speaking. Feel free to email me! renee at tougas dot net.

My main and explicit point is that my writing evolves as I evolve, and I’d like to bring people along for the journey.

And now, the actual essay.

It all started with a move

This is an essay about migration, specifically my own migration. It is not about global migrations, though I do tell one of my ancestor’s global migration stories. This is not an essay about the contemporary migrant or refugee crises. In sharing my migration story, I make no parallels or comparisons to people displaced by war, famine, or environmental change. Though the ideologies and discourses that underwrite these disruptions are discussed.

Migrations are personal, intrapersonal, and interpersonal. Migration is movement within and beyond individuals, families, communities, and geopolitical regions. People migrate from places, and they migrate from ideas. Migration happens at the largest scale of our social and political interactions, down to the most intimate.

This essay explores all that.

Serendipitously, while working on this piece, I was introduced to the subject of Mobility Studies. I’d never heard of it before. However, a very brief read on this interdisciplinary field makes me think that what I’ve written here may belong to that area of study.

I wrote this piece, analyzing my own migrations, to interrogate the source of the “where is home?” question I have been asking myself for nearly 25 years.

“Where is home” belongs to the suite of existential “Who Am I?” questions of origin and identity: Where and who am I from? Where am I going? Where do I belong? What is my identity?

I don’t know how long the question “where is home?” has been part of the human experience. But history might offer some clues. Maybe it started with the religious and philosophical transformations of the Axial Age (500–300 BCE) when, as summarized by John Halstead, “heaven and God became radically “other”, while this world and everything in it became fallen, degenerate, or illusory.”

Halstead quotes the scholar Shmuel Eisenstadt who wrote that “the Axial Age corresponded with ‘the disintegration of the tribal communities and of construction of new collectivities and institutional complexes.’”

During this Age, Halstead writes there was “dislocation of rural peoples to fuel the growth of cities and the accelerating division of labor and accumulation of capital to fuel the growth of a class of religious and political elites.”

It’s easy for humans to assume their individual experience is the Human Experience. I don’t want to make that mistake. And therefore, I won’t make any statements about humans, at large and over all time, wrestling with their sense of home and belonging.

But what I’m comfortable saying is that it’s very possible these questions arise not just out of human’s migratory experiences, broadly, but more specifically are “a function of being human in civilization” (Halstead).1

The Forks, Winnipeg Aug 2022, my own migration was west to east across this continent.

Like every non-Indigenous North American, my ancestors migrated here from other places. My ancestors’ migrations to the land now called Canada happened between the late 19th century and early 20th century as part of the agricultural immigration initiatives. My greats moved at a time when there was little hope or expectation of ever returning to their Northern European homelands.

One hundred years later, when I left central Alberta to move across the North American continent to the New York City metropolitan area of central New Jersey, it was a given we’d be back for the Christmas holiday. Migrations now are not what they used to be.

Humans have always moved around, but colonialism, the industrial revolution, capitalism, the intense globalization of trade, not to mention the increasing human population, have accelerated and amplified human migration. These forces and discourses drove the technology that made migrations easier while also creating and hastening the conditions in some places that have made it an outright necessity.

My own migration and the existential questions of home and belonging fueled by that migration are rooted in a particular context.

My cultural context

None of us exist outside historical and cultural contexts. Full awareness of this fact is important because ignorance of the “macro” situation in our individual and collective experience renders us unable to understand the “micro” experiences of ourselves and others.

As a person who writes about personal experience, this contextual awareness and acknowledgment have become very important to me, as you will no doubt have noticed in the evolution of my writing.

I can identify a few dominant cultural influences in my childhood, from the micro to the macro: my family’s religion which was infused into every aspect of our lives and family identity; the social, economic, and political stories of the western Canadian province where I was born and raised; and more broadly, the rise of neoliberalist-driven policies in the ’70s and ’80s.

All of these amplified a sense of individual agency and responsibility in my decisions. So much rested on me, the individual. In recent years I’ve been working to unravel this.

Five years ago Damien and I lost a house, and the equity we were told we’d build in that house, due to the fallout of the 2008 US housing market crash. We weren’t irresponsible borrowers. We weren’t in over our heads when we purchased it. We were living within our means.

So what went wrong? We bought in 2005 at the height of a hot real estate market. In 2011 when we moved back to Canada, there was no way we could sell the house at its current market value, way below our mortgage. Because we were moving, we couldn’t live in the house long enough to recoup the devastating drop in value. We rented it out to pay the mortgage, basic upkeep, and taxes.

This was not a money-making proposition. There were large maintenance outlays, and the whole thing was a lot of management labour for me. Tenants and property managers came and went until circa 2018, when the tenants just stopped paying the rent. There was nothing more we could do. We foreclosed, and we lost the real estate game, along with millions of other families.

A lot of what befalls us in life is not due to our mistakes, despite what your religion or neoliberal capitalism tells you, but due to inordinate greed and inhuman beliefs and systems whose machinations are antagonistic to human flourishing and well-being.

Over the past nearly 25 years, I have mostly assumed I was haunted by the question “where is home?” because I had chosen to leave where I was from all those years ago.

view from my kitchen window of urban Montreal alley

And who’s to say this isn’t true? However, my overly simplistic and individualistic worldview has evolved into seeing that larger forces are at play in people’s lives, in my life, than just individual choice. And it is these forces and discourses that can drive the question “where is home?” just as much as any personal decision I’ve made.

One of the big reasons I’ve wrestled with the question of “where is home?” is because of the Christian religious teachings of my childhood.

The influence of religion

I was raised with the message of personal salvation, which was secured by individual belief and doctrinal assent. This salvation was for a specific purpose. It was an exit strategy, an escape route from an Earth doomed to destruction.

We weren’t meant to feel at home on Earth. Christians were “in the world but not of the world”. Earth and the relationships here were not my home. Heaven was my true home. And all of human experience and history on Earth was just the selection round for who got in.

Any disorientation, displacement, or sense of things not being right and just in the world - politically, socially, economically, environmentally - were to be resolved in the belief that we don’t belong here anyway. Here on Earth or here in our bodies. Essentially, the world is a messed up and broken place, but we have something better to look forward to, and it is our mission to try to get as many people on board the rocket as possible.

Written like this, I see a lot of parallels in the current 1%-initiated space programs, but at least religion is more equal opportunity. Everyone gets to go, not just the rich and those chosen by the rich.

I don’t think religious belief as an exit ramp off of earth is unique to Christianity. We see the origins of this idea in the cultural transformations of the Axial Age.

This sense of “in the world but not of the world” accompanied me well into adulthood, even after I had intellectually and spiritually rejected the teleological doctrine that the purpose of human experience was for the eventual end of heaven.

Here’s the thing about human feelings of displacement, dislocation, and disorientation. Those feelings are real, and there are a lot of cultural, spiritual, physiological, psychological, and environmental reasons we might experience them.

These feelings can take root in us and will be amplified when we are disconnected and feel separated from ourselves, the Earth/land/nature, and each other.

Our sense of disconnection and separation amplifies the otherness of the stranger and can cause us to react at micro and macro levels with barely imperceptible aggressions at best and horrific exploitations and oppressions at worst. The experience of this pain builds positive feedback loops for further disconnection from Mother Earth and all her inhabitants.

Alienation, disconnection, a sense of separation, and positive feedback loops that amplify those feelings… it’s no surprise that we say we don’t belong or are not at home here on Earth. Religious doctrines are one way of naming the source of pain and finding a resolution. Political doctrines do likewise.

My formative religious experiences amplified the feelings of disconnection from my body, the Earth, and other people, specifically those outside my religion.

This might have been more harmful to me, as I have seen in many other people’s experiences processing their religious backgrounds if I hadn’t been nested in such a loving family and community.

I grew up in exclusionary religion and a nurturing and supportive network of extensive extended relations that constituted a community. My childhood home was stable and demonstrably loving. I knew nothing of displacement, dislocation, and disorientation as a child.

I might have felt like I didn’t belong in the heathen world at large, but I knew I belonged to my family. I’m confident that this is partly because my identity conformed rather well to what was expected and normative in the community. But that acknowledgment doesn’t negate the belonging I experienced.

I knew who I was. I was Renee Toews, beloved daughter of Karen and Derryl, sister to Brad, granddaughter of Betty and Eric, Lorie and Jake. I was a great-granddaughter, a niece, and a cousin. I was, and am, dearly loved and connected to a large web of the living and the dead.

One of my childhood homes, renovated by my parents and added to the Alberta Heritage site registry, featured on puzzle produced by the provincial old-vehicles museum in town.

As an adult, I’ve had to unravel the religious teachings of my childhood, much like a frogged knitting project, to yield a skein of yarn that I could knit into a different spiritual foundation. However, as a child, I never wondered, “where is home?”, nor did I feel out of place or like I didn’t belong. Family was my home.

And then I moved across the continent. And the rupture and the physical distancing from the people I came from initiated the question that has dogged me for almost a quarter century.

My husband Damien and I moved for adventure and opportunity. We wanted to explore, and the times we live in make it relatively easy to scratch that itch. It’s worth noting that I would never have left on my own or in a relationship with a non-adventurous partner. But I did because of who we were together, and Damien’s attitudes and perspectives contributed to my own growth and development. I have become who I am, with the experiences I have, because of who we are.

Beyond personality, individual desires, and the influence of a partner, my migration was made possible because of the technological advances of the time in which I was born. It was undergirded by the economic, political, and philosophical discourses of our modern age, including progressivism, individualism, capitalism, and globalism.

As my story illustrates, these cultural discourses and systems contribute to people uprooting and relocating. Experiences that can amplify the individual and collective sense of dislocation, and disorientation, spurring the question, “where is home?”

Some people’s answer to this question is, “if we all just stayed put we’d be better off.”

This brings me to Wendell Berry, farmer, writer, philosopher, and localism activist.

To be continued, next post.

Footnote:

- For a definition of the word civilization in the context of the questions of home and belonging as discussed in this essay, see Halstead’s The Original Heresy: Homesickness, Civilization, and Transcendental Religion (part 1)

Subscribe to my mailing list for free, to get the next installment of this essay delivered directly to your inbox.

Part of Series

You can subscribe to comments on this article using this form.

If you have already commented on this article, you do not need to do this, as you were automatically subscribed.